Statistics, Probability, and Programming in University Class

In the first session of Professor Abolhasani’s statistics and probability class at the university, we decided to play a game instead of traditional teaching. I have outlined three interesting scenarios that I designed through programming below.

Game One: The Famous Birthday Paradox

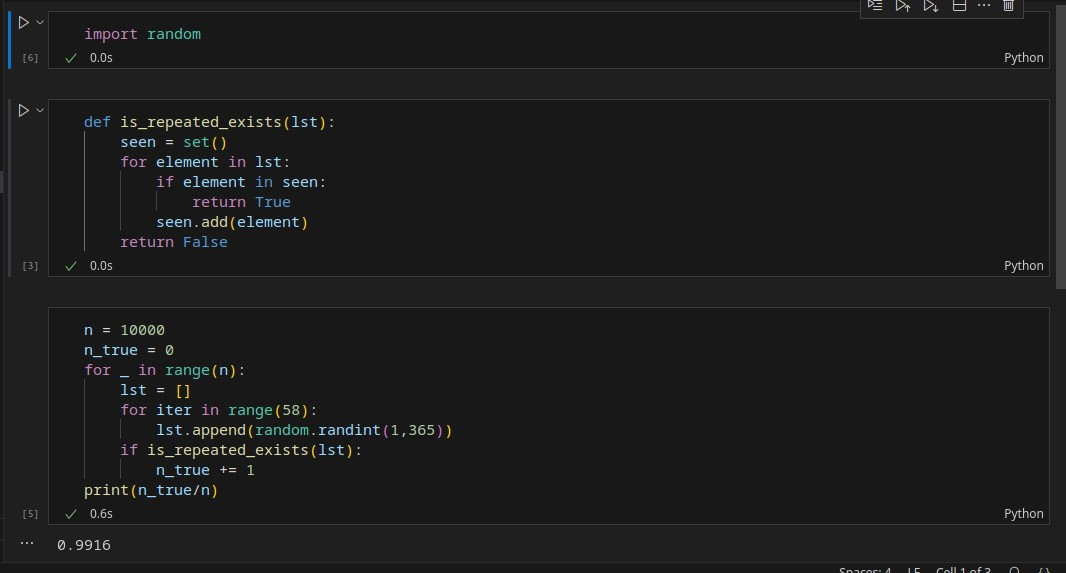

Consider a class of 58 students. What do you think is the probability that at least two people in this group share the same birthday (day and month)? If you were to make an intuitive guess, what would it be? Let’s implement this scenario together through programming! For this, we will randomly select 58 numbers from 1 to 365 and place them in a list. I will also implement a function to check whether there are any duplicate values in the list. We will repeat this process, for example, ten thousand times, and divide the number of occurrences where two values are equal (indicating two people with the same birthday) by the total number of trials (10,000). The result is astonishing! Each time you run the program, you reach a number exceeding 99 percent! Yes, it is quite surprising, but entirely possible and contrary to our intuition! The professor referred to this as the probability of relative frequency.

The class had about 30 students, and the professor asked us to remember the birthdays of two family members. This way, we had 90 people, and then he randomly started with one student. As each student mentioned their birthdays, it quickly became evident that individuals with the same birthday were found! The probability was remarkably high; the professor even offered to bet with us on this topic!

[Wikipedia page on the Birthday Problem]

Game Two: The Son-Champion and Son-Father Matchup

Imagine we have a father, a son, and a champion. The son is going to compete in three sets against the father and the champion. Naturally, the champion has a higher probability of winning against the son compared to the father. We have two models for the matches:

-

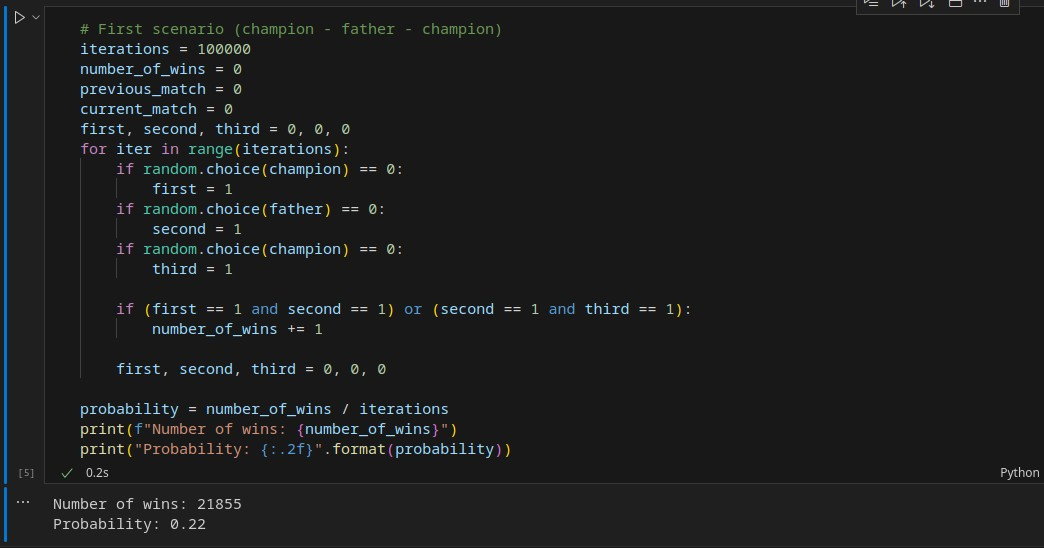

Champion – Father – Champion

- This means the son competes first against the champion, then against the father, and again against the champion.

-

Father – Champion – Father

- Here, the son competes first against the father, then against the champion, and again against the father.

In which model do you think the son is more likely to win two consecutive matches? For instance, in Model 1, if he wins the first two matches against the father and champion, or in the second model against the champion and father? Intuitively, we might say that in Model 1, he competes twice against the champion, and the champion’s probability of winning is significantly higher than that of the father against the son! Therefore, choosing Model 2 for the three-set match seems more reasonable for the son to win.

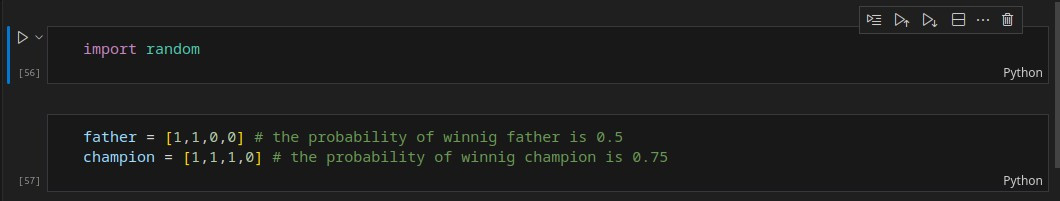

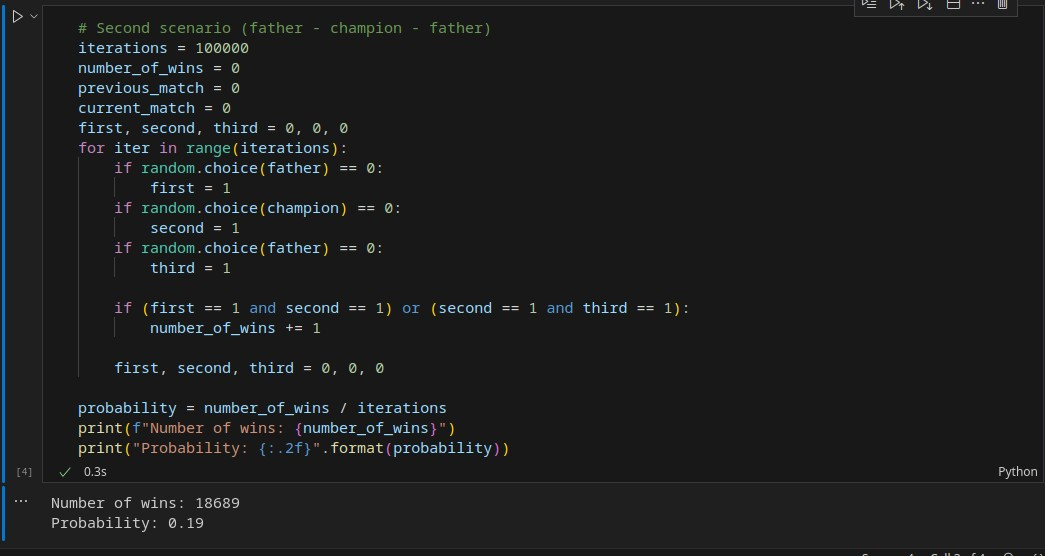

Again, I designed the scenarios through coding, assuming a 50 percent chance of the father winning against the son and a 75 percent chance of the champion winning against the son. I then implemented the scenarios for both models and repeated them a hundred thousand times; the result was again astonishing! Contrary to our intuitive expectations, the probability of the son winning two consecutive matches was actually higher in Model 1 (Champion – Father – Champion)! Although the difference was only 3 percent here, changing the winning probabilities could make the difference more significant; nevertheless, the outcome was contrary to our intuition!

Game Three: The Monty Hall Problem

Imagine you are participating in a television game show. At the end of the game, you have three boxes to choose from; one contains a gold coin, and the other two contain a few dollars. You choose one at your discretion, and then the host removes one of the remaining boxes that is empty (or contains only a few dollars) and gives you the opportunity to either stick with your initial choice or switch to the other box. What would you do? Let’s simulate this problem in Python programming!

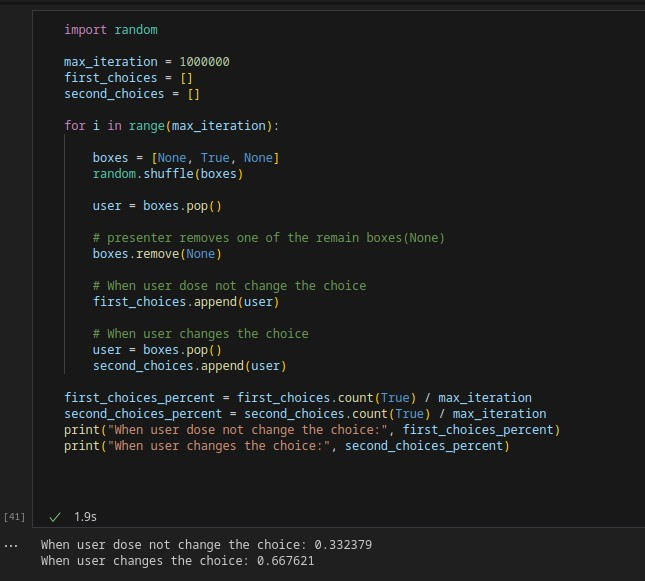

To summarize the code, similar to the previous games, we executed the game multiple times (using a loop) with different participants to ultimately arrive at a valid conclusion. I defined a list of three boxes, one marked as True (indicating it contains the valuable prize) and the other two as None (indicating they contain a low-value prize or are empty). Then, using the shuffle method from the random library, I shuffled them and removed the last element of the list, assigning it to a variable named ‘user.’ Thus, the user or participant makes their initial choice. The host then removes one of the two remaining boxes that is empty, and we stored the user’s choices in two lists: one for sticking with the initial choice and one for switching. We then counted the number of True values and divided by the number of trials. As you can see, when the user switches their choice, they have a 66 percent chance of winning, while if they stick with their initial choice, their chances drop to 33 percent.

Now I realize why, when I was a child watching television game shows, the host encouraged participants to change their choices! :)

[Wikipedia page on the Monty Hall Problem]

In class, one or two other interesting games were discussed; one of them involved the professor holding several pieces of paper and asking students how many there were. Each student had a different guess, and ultimately, by averaging the students’ intuitive numbers, the average was much closer to the actual count!

[Download the source codes (Jupyter Notebook)]

I hope you found this post useful! :)

I didn’t have enough time to translate this from Persian to English myself, so I used artificial intelligence for this task. As a computer science student, I tried to make the most of AI! But not the codes:)